Space Computing 🚀 and Orbit Native Applications

Posted on October 19, 2016 • 6 minutes • 1214 words

Forgive the analogies, I read Breaking the Chains of Gravity: The Story of Spaceflight before NASA and despite a few slow parts, it was a really enlightening read. I couldn’t help but see some similarities with early spaceflight and computing.

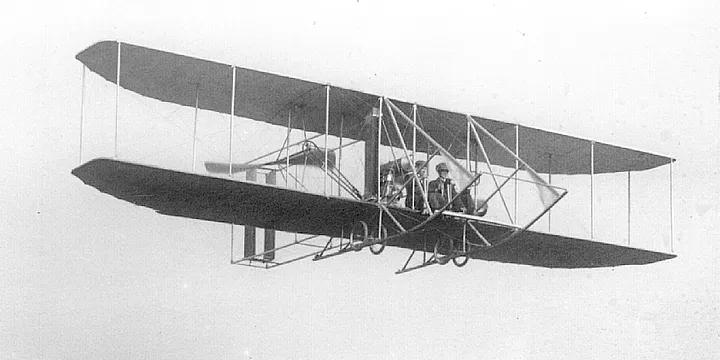

In the early days, flight was about experimentation and lots of smart (and daring) individuals. The early planes were crude and inefficient but they worked and that’s all that mattered. This is also true for almost all early computers, software, and systems administrators. Hindsight is easy to explain how crude something was when we see how “great” things are now.

Wright Model B

Powered flight was a huge boost for the industry. It propelled everyone forward (pun intended). As engineers do what engineers do best, the systems became more efficient, stable, and cheaper. Arguably, powered flight took us all the way to the clouds. We could soar for as long as our engineering and budget could sustain us.

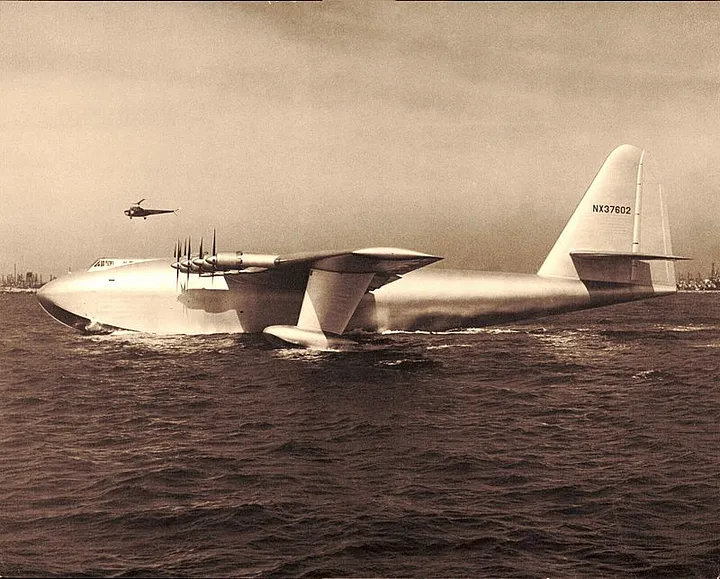

Cloud computing isn’t always faster and better. Sometimes it’s more complex, dangerous, and not the right solution. There are some who push the boundaries and can make it really fast and efficient, but if you need to move thousands of tons of cargo you’re probably going to end up with something not designed for sustained use.

Some people knew planes would be limited to the clouds. Literally. They would never make it past the clouds and out of earth’s orbit with a plane. They needed something more. They needed rockets.

Rockets had their start earlier than I expected. Not just ancient Chinese rockets, but liquid fueled rockets started in 1926. Many of the early rockets were funded with government (not the U.S.) backing with expectations to defend what they had built or take what they thought they deserved. Very similar to the way ARPANET was funded but with different intentions.

The interesting part of rockets, to me, was human flight. When Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier in 1947 (Mach 1) they knew they were on to something. In computing, I would equate breaking the sound barrier to some time around when Docker and Linux containers emerged for the general public. Containers allowed a speed only theoretical before. We could now go faster than ever, but where are we going?

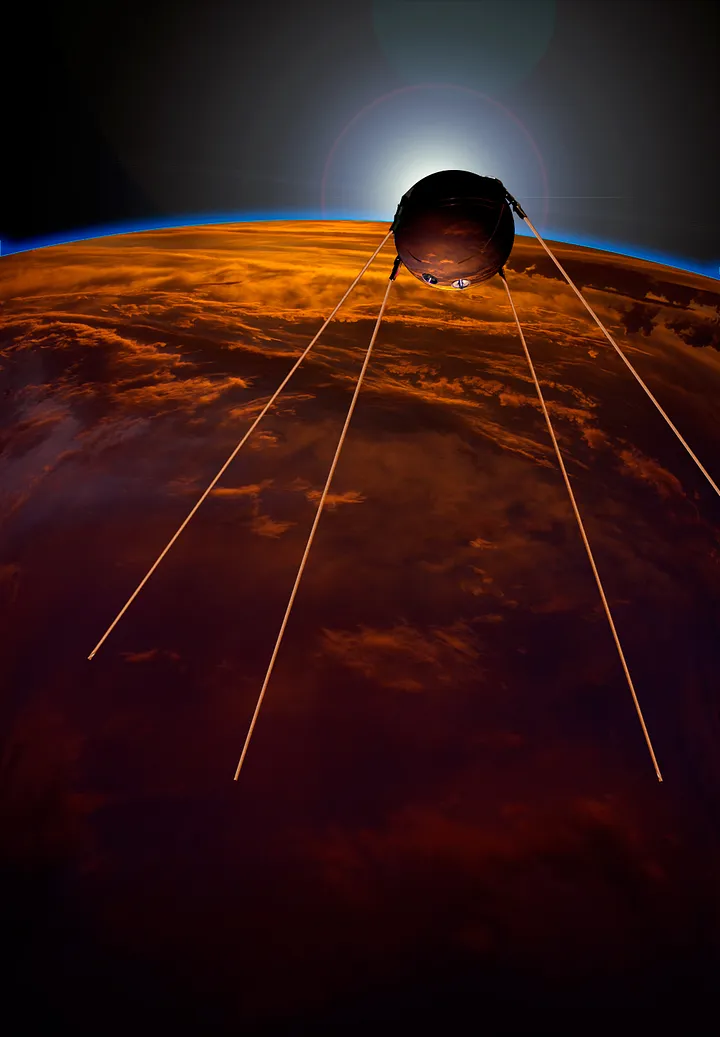

The goal was space. We were not content to stay within the confines of our gravity well and wanted to prove just what could be done. We wanted to send people to space. What we would do there was only limited by our imagination. We could go faster and stay there longer than we ever could in the clouds.

I believe the cusp of space is where we are now with computing. Companies and projects are trying to elevate themselves above cloud computing. This is where containers coupled with automated schedulers have led us. While this infrastructure and application architecture is often called “cloud native” I believe that doesn’t give it justice. Some players are further ahead than others, and there are even a few who are already in orbit. It’s a goal many are striving for and competition is the oxygen fueling the rockets.

The other catalyst to space computing is open source. In the early days of space flight the NACA helped coordinate more than just the national efforts for spaceflight. They also organized and shared knowledge with other countries. This had multiple benefits:

- They were seen as (mostly) non-threatening because it was a civilian group

- They shared designs and data gathered from the successful and unsuccessful flights

- Groups did their own thing (not designed by a central committee) which allowed for failing fast and trying new and innovative solutions

When the Soviet Union wanted to have access to the data the NACA had learned they were told they could join so long as they shared their own flight data and measurements. When the Soviet Union said “no” they were not allowed access in the NACA with the other nations. Obviously, that didn’t stop them, they led the way for many years, but it hurt them in the long run to not be part of the global ecosystem that grew beyond their own “closed source” systems.

Arguably, cloud computing until OpenStack has been fiercely closed source. Amazon Web Services, Google Compute Engine, Microsoft Azure and VMware are closed source for competitive reasons. Space computing infrastructure doesn’t have close ties to any one vendor. In space, you launch your application to orbit and it can circle the globe almost indefinitely.

Of course, once orbit was achieved we kept pushing. We wanted to go to the moon. That is where some are headed now. It’s going to take some time to get there, but just like with spaceflight the acceleration is not slowing down. The amount of time from breaking the sound barrier to putting man on the moon was 22 years. It took only 22 years to go from 767 mph (1234 km/h) to 25,020 mph (40,270 km/h)! Software moves much faster than physics. Even if both are limited to the speed of light.

What will it take to get general public computing to the moon? In my opinion we need the following things:

- Trust: We need to keep launching into orbit and trust we can reliably get there and stay there. The more companies and applications that make it to orbit the more we will trust the engineering that propels us. Arguably, we also need more failures to learn from too. There were many reasons Apollo 11 made it to the moon and not Apollo 1. The Apollo program was the third U.S. human spaceflight program.

- Training: As we control these systems in a new environment the operators need to be comfortable with what all the knobs, buttons, and controls do. It’s a completely different world in orbit where you are constantly falling (weightless). We need astronauts who understand what they’re dealing with and why it’s different from cloud computing.

- Automated flight controls: This is the biggest thing that is still lacking in my opinion. This will be the next big advance in our current thrust to the moon. The next leg of our journey isn’t about sysadmins using software to define infrastructure. It’s about intelligent software that defines infrastructure on behalf of operators. It’s machine learning that knows where you are trying to go and builds it for you. It takes the operator out of the equation. Truth be told, we were never very good pilots to begin with.

The new world of orbit native applications doesn’t mean everyone has to or needs to move there. There are plenty of companies (aeronautics and computing) who make a fortune flying amongst the clouds, and there are many countries who have never sent a single object into space . There are only 3 countries who have ever sent people into space. But that doesn’t mean the rest of humanity doesn’t gain from countries that do take the leap.

There is more that goes into getting to the moon. More research and millions more engineering hours needs to be spent. But once the goal is in site, the only thing between us and space is the clouds.

Although, when I think about it. I’m with Elon. My sights are set on Mars.